Living with Pain

by Lea Kilenga

Photo by Elizabeth Mealey

All my life, I've always thought that one’s ability to watch pain in many cases is a much greater strength than one’s ability to experience it.

I was diagnosed with Sickle Cell Anemia three months after I was born. In a family of four children, I was the third child to be diagnosed with the disease. My two older sisters also had Sickle Cell. This was clear from the physical appearance of our bodies -- our jaundiced eyes, tiny stature and swollen abdomens showed clearly we were sick. At first glance, many often thought it was malaria or malnutrition.

Sickle Cell Disease is a genetic disorder that deforms the normal round red blood cells into sickle-shaped red blood cells. Everything associated with blood and the red blood cells is generally affected, making it a multi-organ disease that makes the patient highly anemic, prone to infections, and susceptible to organ failure, strokes and even death. However, even with all of these, pain is the main characteristic that defines Sickle Cell. This pain is known as a Sickle Cell crisis. It manifests itself mostly in the long limbs and moves to the entire body. This is the kind of feeling that doesn't go away easily. The kind that creeps up unexpectedly, takes over, and handicaps your body and mind into submission. It is an acute or chronic pain that varies from person to person and can only be ameliorated by strong opioids like pethidine or morphine.

I can vividly recall one crisis that happened before my gall bladder was surgically removed. I spent most of my nights beside the toilet bowl and on the floor. This pain was like an intense hot rock in my stomach that wouldn't allow me to swallow anything without 'returning to sender'. That feeling could only be quantified to that of a red hot metal rod stabbed through the upper part of my stomach straight through to my back. The embrace of the cold floor against my tummy was what I needed to get an iota of relief. My mother knew not to touch me, she knew touch somehow exacerbated my pain. She apologized every time the cold cloth touched my feverish body.

Yet, for me, this wasn't as painful as watching my sisters in pain. For some reason, it seemed like their particular kind of pain was much worse than what I experienced. I remember a time when my older sister was in constant anguish. All I could hear were cries from her room where she lay bedridden, limp from the pain; all I could see was a bedside table decorated with prescription pills from her last hospital visit. The worst thing was that nothing I said or did helped her feel better. During these times of great pain, the space between the four walls I called home felt heavy and tense, quiet and sad.

Living with two other siblings diagnosed with Sickle Cell, I had a front row seat to pain. Our house was filled with echoes and screams of discomfort and sometimes long absences to the hospital. Absences that were made permanent as in the case of my oldest sister, who succumbed to the disease. As a four-year-old, I didn't know what had happened. All I noticed was the silence and the empty bed. I only fully came to understand what Sickle Cell was at the age of 14, when I realized that I was not like the others in my class. I had a much smaller body, attended class less frequently, and I was treated like I was ‘special’ - special in the way that a frail, little hatchling is considered helpless. I noticed how the teachers in school whispered whenever I was present. "You shouldn't be too hard on that one, they don't live very long," one teacher murmured.

My sister and I would always cry helplessly whenever we experienced a crisis. A sickle cell crisis knows no time and space, it just attacks. Radiating from source, it travels like a wave throughout the body; like the feeling of a severe toothache or a broken bone amplified a thousand fold in the entire body. The only thing I could do in such situations was contort my body into the least painful position and lie still with fists clenched, praying for relief. While my parents would often try to manage the pain to the best of their abilities at home, we would always end up in the emergency room hoping and waiting for that shot of ‘release’. This was essentially the way of life I knew. The pendulum moved back and forth between my sister and I like a game of ‘catch’, except this game was played with pain. You can win, or you can let it win.

My parents taught me to how to win. They are my greatest heroes. Never in all my life did I see them tire or crack under pressure. I especially loved their ability to see beyond the tears and the heartache. Raising three children with Sickle Cell meant that they had to accept the pain that came with it. "These years with your children will be the shortest and hardest years of your lives," the words from a doctor. They were told that children born with Sickle Cell couldn't live beyond the age of eight, if they were lucky. And those years would essentially be a painful experience for everyone involved. However, this did not deter them from giving us the best life possible. My mother told me that once she got over the denial and self blame (Sickle Cell is a genetic disorder), she was able to understand the disease and better care for us. She treated us like people and not patients, and every pain free opportunity was spent at the beach. Accepting me for who I was helped me accept myself for who I am.

Having a great support system, however, is not the case for many Sickle Cell patients.

Anne is a Sickle Cell patient who was locked away by her mother in an isolated dark room with only a mattress on the floor whenever she cried in pain. Having no access to pain medication and lacking any coping support system, the helplessness and distress brought her mother to seek such dire measures.

Robert, a father who left his wife and children with Sickle Cell confessed to me, "Why should I spend money on 'things' that cry all the time?! And when you take them to the hospital, they don't get well!" He feels he should focus on getting a new family and getting children who have a chance in life. Robert left his wife because he thinks she is cursed.

Pain has a general way of robbing you of your spirit and your will, especially if experienced for extended periods of time. I would forget how life without it feels, forgetting the good times and withdrawing back into my bubble because ‘they’ simply cannot understand. In this bubble, colors appear less bright and days seem much longer. And my voice is silent.

There's only so much I can do or say to make those around me understand the feeling. Pain reduces your words to wincing and moaning. Wincing and moaning is the vocabulary of nuisance, and those who do not understand this vocabulary do not listen. These were the choices I had, be a nuisance or remain silent. I chose silence as the better alternative. In these moments of silence I learned to question and sit in these questions. The biggest one being ‘Why me?’ and ‘Is this important?’.

The closest I’ve come to answering the first question is accepting myself fully. Allowing myself to speak up has given me the strength to meet Sickle Cell warriors where they are, to share with them my experiences and create a safe space that allows them to gain their voices and speak.

Moreover, accepting myself has created space in my heart to empathize with those who rarely receive empathy in response to their pain, a bridge and advocate that seeks to create understanding.

Is there an importance to this pain? Yes and No.

No because with pain there are scars and trauma, scars that linger on even after the pain is gone and trauma that serves to remind you of those moments. Moments you wish never happened, and moments you dread because you know they will come again. Its purpose was lost to me. But zooming out on the life lived so far, I see now what I failed to see before. I see the many lessons that come with the discomfort; the proverbial silver lining around every cloud of pain. So yes, pain is important. It has taught me to be grateful for the good and the bad; to understand that life would only be in balance with both of them; to listen to my body so well that I can take better care of myself and others. To sit in the pain and value those painless moments as they come and go.

Would I trade this pain away if given the chance? No. I don't think I would be the person I am today without it. Strong, fearless and hopeful of a better world because I choose to do and see better. I would not be on this journey that broadens my understanding of the story of self, and of how my own story seeks to expand and allow the stories of a forgotten community to be told.

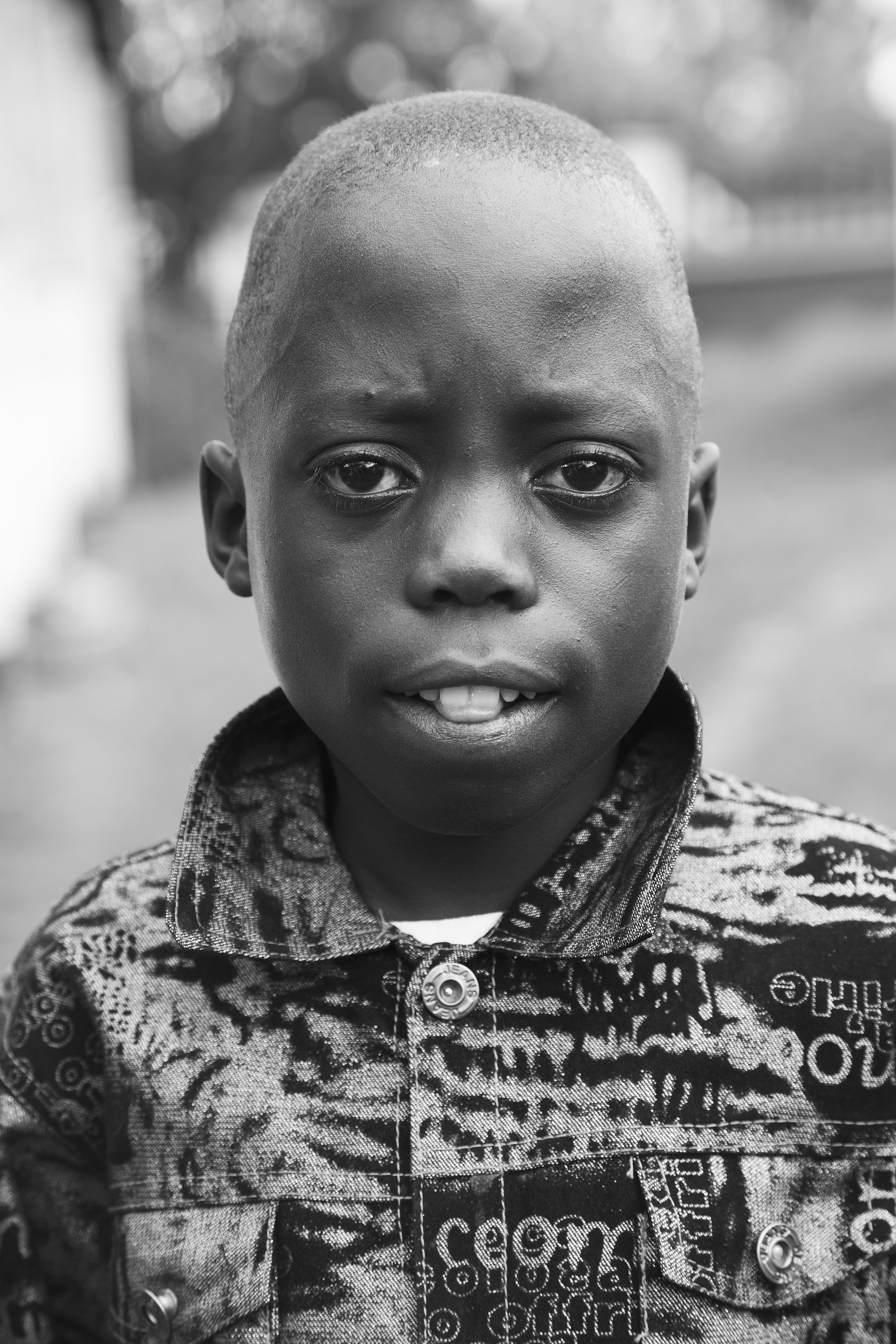

"My name is Rachel I have had persistent leg ulcers, and I am a Sickle Cell warrior.”

“My name is Timothy, I have frequent priapism, I'm on a daily dose of morphine and I'm a Sickle Cell warrior.”

“My name is Charles, my hip bone cannot support my weight, and I'm a Sickle Cell warrior.”

My name is Lea, and I am a Sickle Cell warrior.

Photos of Sickle Cell Warriors who are part of the 10003 Warrior Project, a photographic narrative that Lea and her team hopes will enable them capture 10, 003 raw real-time portraits and stories of sickle cell warriors around the country. These photos are by Lea's brother, Paul Masamo. For more of his work, please visit his personal website.